An Intro to Grounding: Types of Electrical Grounding and What They Mean

Originally, the plan was to write about another topic.

But after some thought and reflection, it occurred to me that there is very little information about electrical grounds and grounding.

If you’re an electrician, you’re hopefully familiar with grounding in homes and buildings (Earth grounding). But there are different types of grounds and not a lot of information is available to non-construction oriented electronics enthusiasts.

Even many engineering texts seem to completely ignore the subject and fail to give any practical explanation or meaning to the term ground.

To make matters worse, electronics enthusiasts often confuse and incorrectly interchange the symbols for the different types of electrical grounding.

For example, you may think that your car has a “ground”. The truth is your car sits on four insulators and is not at all electrically connected to the Earth.

So what does all this mean? Let’s take a closer look at the types of electrical grounding and what the term “ground” really means.

Electrical Grounding 101

Technically, the term “ground” refers to a physical connection to the Earth. This symbol is shown in part (a) of the figure below. All too often, this symbol appears on circuits that do not connect to the Earth at all.

This is the one that many electricians are familiar with. In your home, one (or maybe more) 8 foot copper coated rods are driven into the Earth. You’ll often find this near the meter outside. A copper wire connects the ground rod to the main electrical distribution box (or panel).

This symbol belongs on your home wiring plan. It can also go on a schematic diagram to indicate the Earth ground of an antenna system. You may also notice that your telephone and/or cable company also uses this rod as a ground for their systems.

Why does this work?

The Earth is an extremely large conducting mass in which there is virtually zero resistance between any two points. Think of it as a giant reservoir of charge. Since it is electrically neutral, an equal number of positive and negative charges are distributed throughout its entire mass. Because of this, the Earth is at zero potential.

The National Electrical Code mandates that the resistance between this rod and Earth be 25 ohms or less.

Another popular electrical grounding spot in buildings is the cold-water pipe, since the pipe that supplies water to your home is likely buried in the ground and conductive.

Not planning on connecting your latest microcontroller project directly to the Earth?

No problem.

I’ve already alluded to the fact that there is more than one type of ground. As an electronics enthusiast, you’re likely to see three different types of grounds that all have different meanings and schematic symbols.

Electrical Grounding: Chassis Ground

In the figure above, part (b) depicts the chassis ground. This is the correct symbol to use when referring to your vehicle. It can also indicate things such as the frame of a plane, or the metal box that you’re going to enclose your project in.

In your car, the negative terminal of your battery connects to the frame and/or engine block. Thus, the entire metal body of the car which is at the same potential (hopefully) of zero volts is the electrical reference point (a.k.a. ground, or more correctly, chassis ground).

In your widget that lives in a metal box, this is usually done with a ring terminal and a screw.

Note that if your creation runs on batteries you may not even need to use a chassis ground.

We’ve all put our projects in plastic boxes before, which brings us to the next and most common type of “ground.”

Electrical Grounding: Circuit Common

Part (c) of the figure above depicts the symbol for the circuit common. This is really just a common reference point in a given circuit. This is the symbol that you should use most often rather than the other two for most of your projects. On printed circuit boards, this is often the large-area copper foil layer (a.k.a. ground plane) of the board.

Sometimes, you’ll see a letter inside the triangle part to notate different types of returns (like the signal common).

This is because a condition known as a ground loop (technically, a common loop) can arise when commons are shared between, say, power and signal.

So why is this type of “ground” technically referred to as common?

Become the Maker you were born to be. Try Arduino Academy for FREE!

When we measure voltage, we always measure it with respect to some other point. For example, when we measure the voltage drop across a resistor, we are measuring the voltage on one node with respect to the other node, with the resistor sitting between the two nodes. This is an example of measuring a voltage drop “across” a resistor.

To say we’re measuring voltage a specific point doesn’t make sense as voltage is a potential difference and having a difference of any kind implies there are two things to compare. Rather, if someone asks you to measure the voltage at point A in circuit, they mean at point A with respect to the circuit common.

For all the uber-nerds, the formal scientific definition of voltage is the equation below.

Vba = – ∫ E ∙ dl

Where the integral is from point a to point b, E is the electric field, and dl is an infinitesimal increment of displacement.

This equation uses calculus and is one you may be familiar with if you’ve studied engineering. The typical enthusiast should not have to worry about this, though you should feel free to investigate further if that sort of thing interests you.

Often, you’ll find yourself measuring voltage with respect to “ground” or the common point of the circuit. This is because this point should be at zero potential or 0 V. An exception would be measuring the voltage across one resistor in a network of resistors.

Confused? Check out the diagram below.

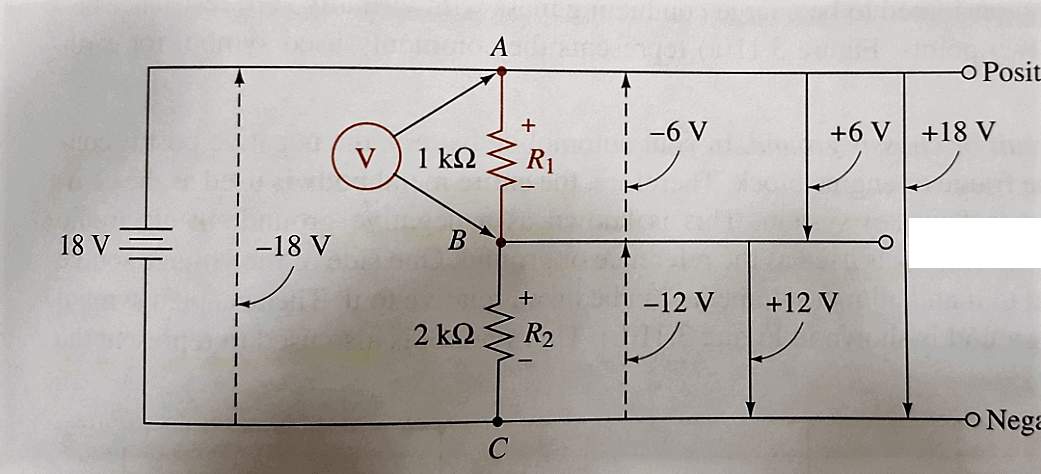

In this picture, point C would normally be the circuit common. Notice how point C connects to the negative terminal of the 18 V battery. When measuring voltage, you normally place the negative probe of the voltmeter on the circuit common.

Resistors R1 and R2 are a “network” so if I want just the voltage across R1, point B would become my reference rather than point C.

Why?

Because point B is lower in potential than point A. Put another way, point B is more negative than point A. Of course, resistors don’t actually have a polarity. The + and – symbols are there to represent the voltage drop and the fact that there is a potential difference between points A and B.

If we were to put the negative probe on point B and the positive on point C to measure the voltage across R2, we’d get the -12 V shown by the dotted arrow. If we were to measure the voltage across R2 the conventional way (with point C as the reference), we’d get +12 V as the solid arrow shows.

Notice that the absolute value of the voltages is the same regardless of how we orient our meter probes.

Of course, if we were to measure the voltage across both resistors, we’d get the full 18 V (or -18 V if the probes were reversed).

Uncommon Commons

So far, the circuit common has been associated with the most negative part of the circuit, usually the negative terminal of the battery or power supply.

The truth is the circuit common can be anywhere. The picture below from the 4th edition of Practical Electronics for Inventors illustrates this concept (though the ground symbol is technically incorrect).

Take a look at the three terminals in each picture. The first part of the picture has the circuit common tied to the negative terminal of the lower battery, as expected. Each individual battery is supplying 1.5 V with both in series supplying 3 V.

However, the common in the second picture is now in between the two batteries. Notice how each battery is still 1.5 V, but rather than obtaining 1.5 V and 3 V as in the first picture, we obtain +1.5 V and -1.5 V. The battery connection is the same, so why is this possible?

Simply because the common, or reference point, is in a different area. Remember, when you measure voltage, you’re measuring the potential difference between two points. Often, one of the two points will be the circuit common. If the common point moves, the voltage may be different even if the circuit is the same!

Most often, you’ll be working with circuits similar to the first picture.

But split power supplies (like the second picture) are somewhat common in audio and other types of circuits where sinusoidal signals swing between negative and positive voltages (relative to 0 V, of course).

One last thing to notice is that the total potential difference in both circuits is 3 V, regardless of where the reference is. After all, two 1.5 V batteries alone are only capable of producing a maximum difference of 3 V.

Grounding for Safety

Before we wrap up, we need to take a quick second look at Earth grounds.

Besides acting as a reference point, Earth ground is there to protect you from electrical shock.

How?

As an example, let’s say that a hot wire inside your dryer somehow comes into contact with the inside of the dryer’s metal body. Without an Earth ground, touching the dryer may cause shock or even death.

However, since the case of the dryer connects to Earth ground, the current shunts away saving your life and likely tripping the breaker due to the short. In fact, a hot to ground short will usually trip the breaker the instant it occurs.

Grounding also helps with electrostatic discharge. So, when you take a walk across the carpet, the charge on your body (which can be tens of thousands of volts) goes to ground rather than frying the ICs in your gadget.

Are You Grounded Yet?

Grounding can be a complex and mysterious subject to many. All too often books, educational courses, and tutorials either quickly gloss over it (if they cover it at all) or do a poor job of explaining it.

Hopefully, this post removed some of the mystery surrounding electrical grounding (rhyme intended).

As with most things in electronics, there is a lot more to say about grounding. Perhaps a future post will revisit the topic.

Meanwhile comment and tell me what your biggest questions on grounding are. That way, I have some ideas on what to write about!

Become the Maker you were born to be. Try Arduino Academy for FREE!

Electronics Tips & Tutorials Sent Directly to Your Inbox

Submit your email & you'll get:

- Exclusive content that I don't put on the blog

- The checklist 10 mistakes all electronics enthusiasts make (& how to avoid them)

- And more!

I would like to See anarti about how to proper ground a home lab like When ro use the Erath gnd on a Dc power supply (the greeN banna plug, the best way to gnd, o’scopes, and funct generator. Do they all need to be fixed to a single point? Should it be a walL-outlet. I live in a 100 year old house and elecity outlets are hard to come by, and may dOnt have the 3rd gnd plucg. I have had to cascade maNy exTention cords and power steips. And i feel that some of the polarity on outlets are Reveresed. I have picked up a 3 progN polarity/gnd checker but i dont know if i trust it.

I an getting into HAm radio a rf experiments and i know that grounding will be my biggest problem. How sould i design a grounding system tHat i can plug in all my equpment to ensure safty, and eliminate gnd loops in my radio equpment and eXPerements.

I also do a failr aMout of SOLDERING of esd sensitve parts. I have a Second Hand wrist strap and the “black box” to plug my wrist strAp inot, but as of now its conne directly to a copper rod driven into the the Backyard rigHt out side my widow in my work room.

Am i on the right track?

Best regards and look for word to more articles.

I appreciate your interest in my article. Grounding in the home is very important for safety. Unfortunately, I’m not a licensed electrician so giving advice on how to wire your home would be a liability for me. And I cannot drop by to see what you have going on there. I’d suggest contacting a licensed electrician in your area. You’ll have to pay them, but at least you’ll know it’ll be done right.

I agree. It’s better to look for professional electricians because they are reliable.

I have run across a lot of older homes without ay ground, either at the breaker panel or outside at the meter. This is a real hazardous, for both the service man and the homeowners. Non polarized plugs can often present the full potential between two devices. Even older homes used the old gas light piping as a common and only pull a hot wire to outlets.